Something truly magical occurred the other night. That experience has inspired me to lead a series of online summer campfire sessions online. I hope you will share my excitement. Sometimes it takes a lot of theory to explain something so natural.

Theory

For generations, established musicians and athletes have recounted the lessons learned riding the bus with seasoned veterans. This may not be where they learned the specific skills of their vocation as much as what it means to be a ballplayer or artist. Tall tales, legends, and practical advice are shared, tacitly and directly, without a formal curriculum. When one looks back upon the knowledge “dropped” at just the right moment they realize that it was within the zone of proximal development. The “lesson” was just slightly out of reach of the newcomer – yet retained and recounted for a lifetime once the recipient matures sufficiently to recognize the critical wisdom imparted at that pivotal moment. Such lessons are big and small. A raised eyebrow, pat on the back, being lent a book to read, or being tossed across a room are some of the myriad of pedagogical strategies employed by more accomplished colleagues.

Even if motivated by a mere desire to hang out with someone you admire, such experiences provide the context for the assimilation and accommodation processes required for personal knowledge construction. (learning) Such cognitive development happens inside the learner but is often situated within a social setting. This is the basis of constructivism.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger attempt to distinguish themselves from Piaget’s notions of intellectual development by asserting the importance of the social setting. For them, knowledge is always socially constructed, while Piaget was open to that idea, but neither stated it definitively or dismissed personal learning. Lave and Wenger introduced the idea of legitimate peripheral participation (LLP) to describe how newcomers become experienced members and then eventually old timers of a community of practice. As “newbies” develop mastery, their participation becomes more essential to the functioning of the community and are valued for their expertise. Apprentices evolve into mentors who can bestow legitimacy upon newcomers once they demonstrate the habits and commitments valued by the community. It is the very access to expertise that aides the developmental process. Lave and Wenger’s LLP theory suggests that without such access to expertise and proximity to examples of practice, learners will experience limited growth. Learning is growth.

“Riding the bus” is a prime example of LLP. By initially participating in casual or low-risk activities such as observation or listening, rookies learn the expectations, vocabulary, shared traditions, and mission of the community. Other communities of practice have their version of “riding the bus” or “the locker room.” Many musicians call this “the hang.”

The hang is what I love about jazz musicians; they have perfected the hang and raised it to an art form. In fact, it is not uncommon for the hang between or after sets to be as profound as the performance on-stage. The hang is the glue that holds any community of practice together. It provides nourishment and sustenance. Access to the hang is an invitation for newbies to assess how they measure up and if they wish to be a member of that guild.

Fans engage in LPP by observing the interactions of musicians young and old at different levels of development during a performance. If they can summon the courage, they sneak backstage to peek into the green room. Stand in the doorway of the kitchen at the Village Vanguard between sets or at the end of the night and witness the camaraderie, serious planning, and hijinks of the musicians blowing off steam or preparing for the next set. Old friends, mentors, and aspiring talent come and go in a ballet of mutual respect, tradition, and reciprocal inspiration. One’s knowledge, talent, reputation, willingness to imitate the behavior of the experts, and humility are all part of the price of admission to a community of practice. Sometimes, love and respect for the what the elders do is sufficient for being tolerated on the periphery of the hang. Persistence is a form of dues paying that may bring you closer to the center of the action over time. Chutzpah is often rewarded by an invitation to join all sorts of communities.

In the hang, expertise and relationships are fluid and not always hierarchical. Depending on a particular situation, teacher/student or mentor/apprentice relationships will switch at the microlevel since expertise is distributed and embodied in various members of a community. Newbies often have something to teach the veterans even within a group sustained by legitimate peripheral participation. Papert wrote about the power of the Brazilian samba school as a metaphor for ideal learning environments that appear to resemble “school,” but benefit from all of the best aspects of LLP. Across Brazil, community organizations exist for the purpose of performing large, colorful, and spectacular dances for the annual Carnival celebrations. In the samba school, you are part of something larger than yourself. Young and old gather to dance together. Traditions are passed down. New dances are invented and perfected. Along the way, members of the LLP create something of great complexity only achievable in such a democratic setting rich in joyous and purposeful effort.

Me

Even though my schooling experience was often unpleasant, unproductive, and complete with bullying (by kids and teachers), from third grade on I could always find a teacher to hang out with. I remain in touch with some of those educators who long ago became cherished colleagues and friends.

When I became interested in education, educational computing was where you would find the smartest, bravest, and radical thinkers. Making the world a better place for kids has always been my objective, so I pursued the expertise leading such efforts. Luckily, as in other seminal moments, unlikely mentors came into my life at precisely the right moment and ushered me into spaces I otherwise could not have accessed. I shared some of those apprenticeship experiences in my most recent TED Talk.

At twenty-three years old, I drove my Toyota Corolla to MIT for the international Logo ’85 Conference. I parked the car and before I could lock the doors, a woman yelled, “Hey kid! Come to dinner with us!” That woman was Dr. Cynthia Solomon, one of the inventors of Logo and the mother of educational computing. Many of the people I met that evening have not only become my greatest friends, mentors, and colleagues, but they participated in last week’s online Constructing Modern Knowledge Celebration. Cynthia Solomon and Brian Silverman have been faculty treasured members of the CMK institute faculty for twelve or thirteen years. The expert educators and inventors I met between 1984 and 1986 not only taught me how to teach and learn, but we have traveled the world together and taught a bazillion educators along the way.

There was one memorable evening in particular that changed my life. A few months after the Logo ’85 conference, I flew cross-country to attend the first West Coast Logo Conference in Los Angeles. I remember the opening cocktail reception vividly, Brian Silverman and David Thornburg (who would also become a dear friend and cherished colleague) were engaged in a spirited conversation about Ada Lovelace. I had never seen anything like it. I made sure to listen carefully and stay on the periphery of the conversation while thinking to myself, “I want a life of this!” I wanted to spend time with intelligent people and argue about interesting matters, large and small. While silently participating in that conversation, my worldview and trajectory were transformed.

Communities of practice thrive in the interstitial spaces – on the bus, in the locker room, at the bar – not typically in the classroom.

Us

I often fear that educators are “hang deprived.” Sure, they attend conferences and have sheroes or mentors, but where are the rich multigenerational traditions built, sustained, and shared? Student teaching is a form of apprenticeship, but how often does that master teacher become a lifelong colleague? (In many cases, they just surrender their class to the newbie and split.) Where does an educator enjoy the inspiration, love, or rejuvenation found in the sort of “hangs” described above? What are the costs of such deprivation?

The annual Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute (CMK) was created as a space where experts, novices, and practitioners of all levels in between assemble to work on projects that matter to them. No one sorts folks into ability groups or takes any notice of what a person teaches, where they come from, or what they know. They’re just part of the “the hang” where everyone works on projects for four days, surrounded by different levels of expertise on-tap as needed or learn from through careful observation and casual encounters.

The project work at CMK is the “official hang.” Informal conversations with new colleagues over meals, walks with faculty members, and sneaking conversations with our remarkable guest speakers represent the hang within the hang. I know what it has meant to my development to not only meet most of my education sheroes and heroes, but to actually get to know them. There is no greater joy than sharing these friends and colleagues with educators who get to say, “I spent time with ___,” rather than, “I heard ___.” There are countless stories of participants engaging with experts, visionaries, leaders, and inventors at CMK while no one else was looking. Such experiences can be life-altering.

The conversations at last week’s virtual Constructing Modern Knowledge Celebration were an opportunity for CMK faculty and alumni to reflect upon their experiences at our institute and share the ways in which our samba school impacted their lives. Those personal epiphanies were enormously gratifying. After two such ninety-minute Zoom sessions, the last event featured an Ask Me Anything session with the legendary education author and ingenious provocateur, Alfie Kohn. Alfie engaged in conversation with the assembled educators, as he has done three times at CMK and challenged our thinking for more than an hour.

Then something even more extraordinary occurred. After we said, “goodbye,” to Alfie and officially ended the day-long event, some people didn’t leave. Old friends I hadn’t seen in twenty-five years, former grad students, CMK faculty, mentors, and friends of mine stuck around to hang in Zoom for the next two and a half hours!

Best of all, we didn’t retreat to a “private room” but carried on our mixture of the profane and profound in full view of the “audience” who stuck around on the perimeter of the circle, just like I had during the Ada Lovelace discussion all those years ago. Like most, this hang was filled with humor, life experience, questions, arguments, reminiscing, advice, and love. Occasionally, someone from outside my inner circle of friends would ask a question or contribute to the conversation, but several dozen other educators just lurked. That thrills me!

In an online context, lurking is a form of apprenticeship. It is legitimate peripheral participation. That is why, in this period of chaos and uncertainty, it is so necessary to share such opportunities for conversation and the sharing of learning stories. My online Ask Me Anything sessions are my contribution to educators hip enough to participate, even if participation consists entirely of lurking (for now).

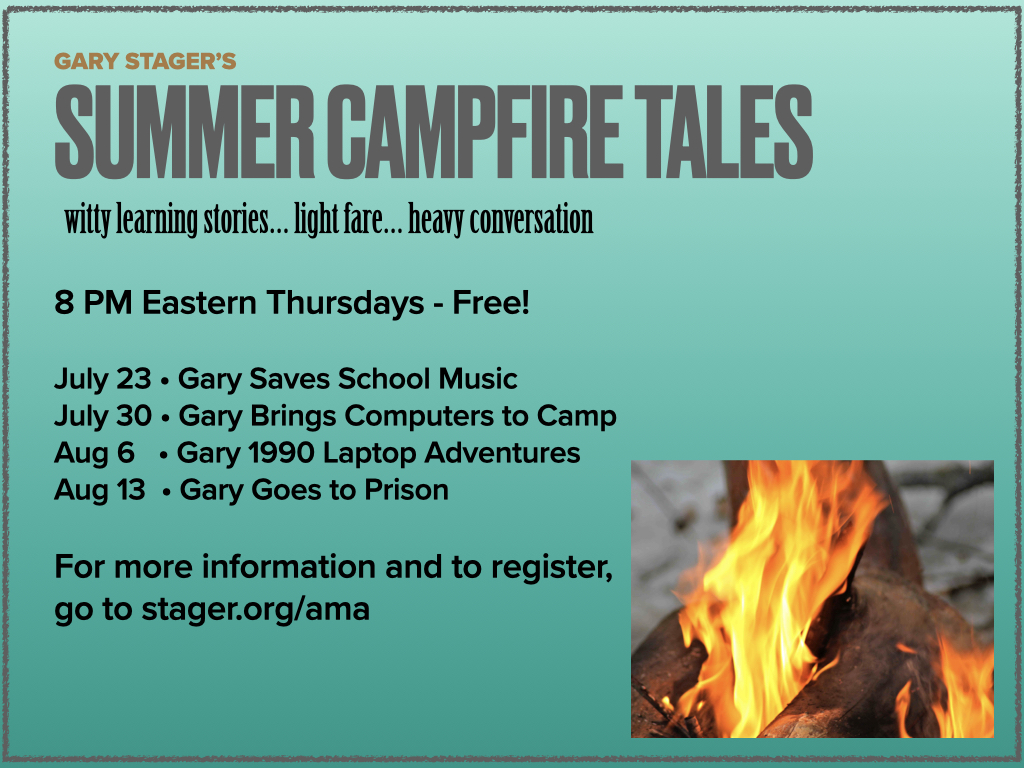

Since the start of the pandemic, I have hosted six Ask Me Anything sessions, four with guest speakers, plus the Constructing Modern Knowledge Celebration. Since it’s summertime, I’ve decided that the next four Thursday night sessions will offer lighter fare. Each Thursday, I will begin the proceedings with an evocative tale from my career and then hang with anyone interested in discussing anything.

Won’t you please join me and invite your friends too?

For more information and to register, go to stager.org/ama

References

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: children, computers, and powerful ideas. New York: Basic Books.

Legitimate Peripheral Participation. (2020, July 20). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Evolutionary_history_of_life&oldid=925898335

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.