Twenty years ago this past summer, I led professional development at the first two schools in the world where every student had a laptop. You read that correctly; 20 years ago! Those two Australian schools, 1 private and quite well documented – Methodist Ladies’ College (MLC) and one public and lost to history – Coombabah State Primary School, finally realized Seymour Papert and Alan Kay’s 1968 vision of personal computing. Every child had their own laptop and learned to program in LogoWriter as a way of exploring powerful ideas across the curriculum. Their teachers, predominantly computing neophytes, learned to teach programming and as a result thought deeper about thinking. We had little doubt about what children would be able to do, but expectations were high for teachers.

Twenty years ago this past summer, I led professional development at the first two schools in the world where every student had a laptop. You read that correctly; 20 years ago! Those two Australian schools, 1 private and quite well documented – Methodist Ladies’ College (MLC) and one public and lost to history – Coombabah State Primary School, finally realized Seymour Papert and Alan Kay’s 1968 vision of personal computing. Every child had their own laptop and learned to program in LogoWriter as a way of exploring powerful ideas across the curriculum. Their teachers, predominantly computing neophytes, learned to teach programming and as a result thought deeper about thinking. We had little doubt about what children would be able to do, but expectations were high for teachers.

At MLC, I was trusted to do whatever I thought would improve the school. I worked in classrooms with teachers as my apprentice so they could see through the eyes of their students and their laptop screens what modern knowledge construction looked like. I ran workshops, took dozens of teachers off-site for multiple-day immersive learning adventures, worked across K-12 and had complete 24/7 access to the very busy school principal. I recently asked MLC Principal David Loader what he was thinking when he hired a 27 year-old American with no formal academic credentials, paid him to work in his school for months at a time and have complete authority to do whatever he felt was right, regardless of the risk? David at first looked confused by the question and then matter-of-factly said, “I gave anyone who showed initiative the same level of authority.” He then rattled off the music, art and catering teachers who were indeed given free reign to do the impossible on behalf of kids.

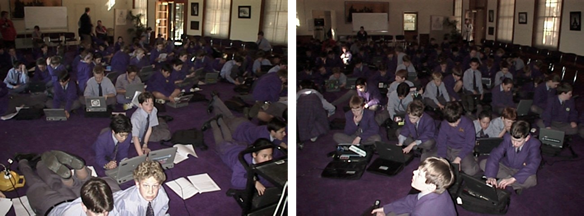

MLC quickly became recognized as one of the best schools in the world and led the way for other schools eager to embrace personal computing. Within a few years, hundreds of thousands of Aussie students had a school issued laptop. I had the great privilege of working with dozens of Aussie “laptop” schools in the early 90s. Along with my colleagues, we invented the future. My work in schools where every student has a personal laptop computer has taken me around the world several times.

MLC quickly became recognized as one of the best schools in the world and led the way for other schools eager to embrace personal computing. Within a few years, hundreds of thousands of Aussie students had a school issued laptop. I had the great privilege of working with dozens of Aussie “laptop” schools in the early 90s. Along with my colleagues, we invented the future. My work in schools where every student has a personal laptop computer has taken me around the world several times.

My work at MLC is well chronicled by Bob Johnstone in his book, Never Mind the Laptops: Kids, Computers, and the Transformation of Learning, and in a recent essay I wrote, “Hard and Easy,” as part of Pamela Livingston’s book, 1-to-1 Learning, Second Edition: Laptop Programs That Work. In 1995, ASCD published an article I wrote, Laptop Schools Lead the Way in Professional Development, in Educational Leadership. On the 10th anniversary of my work in laptop schools, I produced a “Laptop Self-Assessment” rubric to determine how a particular school measured up to the goals my colleagues and I set back in 1990. MLC published a book in 1993 documenting their approach to education and educational computing, Reflections of a Learning Community: Views on the Introduction of Laptops at MLC. The entire book has been preserved here.

Since my early work at MLC, Coombabah and other Australian schools, I’ve worked extensively in “laptop” schools around the world. (Subscribe to my occasional newsletter to learn about new 1:1 videos and other resources to be put online in the near future.) I collaborated with Seymour Papert and advised his colleagues in Maine prior to the law providing a laptop for every 7th and 8th grader in the state. I inspired and collaborated with the Eastern Townships School Board in Quebec where 6,000 3rd-12th graders have MacBooks and I was a member of the One Laptop Per Child Foundation’s Learning Group.

In April of this year, I had the privilege of celebrating my 20th anniversary of 1:1 and work in Australian schools as the keynote speaker at the Australian Computers in Education Conference in my adopted hometown of Melbourne, Australia. This evening I will be the keynote speaker at the European Laptop Institute in The Hague.

In a few weeks I will return to Seoul, South Korea to work at The Chadwick International School, a magnificent new progressive international school that will eventually serve K-12 youngsters from Korea and abroad. In a few weeks, my colleagues and I at Chadwick will once again change the world when every student from 1st grade onward will have their own personal Macbook computer. Robotics, programming and deep project-based learning across the curriculum will be the hallmarks of Chadwick’s approach. We will move past the low-hanging fruit of information access and language arts and use the computer to create new learning opportunities and amplify student potential across the entire school.

Not since the early 1990s have I had the opportunity to work in a school and mentor teachers so closely over a long period of time as I will at the Chadwick International School. I have spent the past six months or so as a consultant helping with the planning process; including policy issues, purchasing, professional development, visioning and curriculum integration. Look out for great things coming from this exciting school.

Within hours of returning home from South Korea, I fly to to speak in Peru, where hundreds of thousands of children own an XO personal laptop. I’m excited to get the chance to work with my old friend (from the mid 1980 Logo days) Oscar Becerra

December 2-3, I’ll be in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to be the keynote speaker, along with Dr. Chris Dede, at the Great Lakes 1:1 Computing Conference.

At some of these upcoming conferences I will not only be delivering my keynote address, Ten Things to Do With a Laptop: Learning and Powerful Ideas, but also brand new keynote, Twenty Lessons from Twenty Years of 1:1 Computing. That session, dealing primarily with leadership and policy issues was presented recently at the ISTE Conference, National School Boards Association’s Annual Conference and the NSBA Technology + Learning Conference.

From the very beginning giving a laptop to every child seemed like an inevitability. Computers were getting smaller, cheaper and more powerful. Of course children would have their own before long.

For the first time in 20 years (now 40) we had the platform available to begin realizing the ideals of Dewey, Kay and Papert. There was never any talk of experiment or pilot or project or initiative. Laptops were purchased for students because it was on the right side of history and the right thing to do.

At the recent Australian conference a Monash University lecturer told the audience that we should go slow with 1:1 because the jury is still out and the evidence yet to accumulate to justify the investment. The moderator, Jeff Richardson of Trinity College, snatched the gentleman’s iPhone, asked the audience how many people live in homes where there are more computers than humans and then suggested that children deserve no less where they spend most of their waking hours. The dirty little secret is that thirty years after microcomputers came into most Western schools, children get to use one for less than an hour per week. The Australian moderator asked me if I’d like to contribute anything to the suggestion.

I told the Monash lecturer that, “the first doctoral dissertation demonstrating the efficacy of 1:1 computing was published in 1991 in his department.” I own a copy. It’s time to move on! The kids deserve nothing less.

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.

One of the schools that I was appointed Head of IT at many years ago, got me to spend 18 months on a research project focusing on the efficacy of 1:1 computing before it would fund any of my projects. Meanwhile the skill levels dropped and opportunities missed. The issue was never the effect of the program, it was whether it was being supported properly by the school executive and whether teachers had the skills to effectively support the program. Meanwhile, 5 years on, the kids have iPhones that are more powerful than those computers that we used at MLC and the school is still questioning the effect of computers on learning.