Many of my readers and colleagues know that I have a knack for questioning deeply held assumptions and myths involving education. I also hold positions that others might find extreme. For example, I think curriculum, in all of its forms – especially heavy-handed nonsense like “Common Core – is a terrible idea. I don’t mean bad curriculum is a bad idea; I mean that curriculum itself is a bad idea. (click here for an explanation)

That said,I do not promote anarchy or even believe that “curriculum-free” pedagogy, such as unschooling, result in irresponsible chaos.

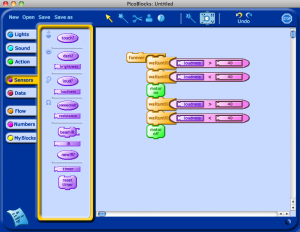

For the past several months, I have been working a few days a week as a S.T.E.M. consultant at a school in Los Angeles. The goal is to improve the quality of teaching in the school and I am doing a lot of modeling in classrooms. A couple of weeks ago, I began using robotics in the 5th grade class. I have lots of objectives for using my favorite robotics materials, Pico Crickets, but here are three big ones. I could list a bazillion sub-skills and affective objectives, but I will spare those details.

- Specific science, engineering, mathematics and programming concepts come to life in a tactile fashion.

- Students develop important habits of mind and inquiry skills by tinkering, invention and complex open-ended project work.

- You can learn an awful lot about individual student learning styles, talents and prior knowledge by working alongside them during problem-solving activities. You also learn a lot about their prior educational experiences.

I first introduced the Pico Cricket materials to the kids by quickly showing the special parts in each building kit, asking them to “bunch up” in groups and recreate one of the projects suggested in the pictorial Pico Cricket placemats that come with each building set. After no more than two or three minutes of instruction, I circulate around the room, make suggestions, ask questions, troubleshoot hardware and remind kids to “ask three before me.” I seize the teachable moment and introduce a nugget of information when and where it is needed. Occasionally, I’ll ask one student to pass that along to others or just announce that “Samantha knows how to do X.”

After a session or two of recreating, personalizing and embellishing the project starters, I asked the class to invent new toys. One group built a bowling machine that sent a ball down an alley to knock down pins. Another built a barking walking machine inspired by a book I made available. Two teams approached gumball machine design in different ways, with one even making the machine coin-operated.

Another student was teeming with ideas and enthusiasm, but less accomplished at consensus building with peers. So, I gave him his own building set to work with in an effort to amplify his his strengths while suggesting that he will need to develop greater ability to collaborate. He was the first to program his Pico Crickets and became an asset to other kids who needed to learn to use the Scratch-like programming software.

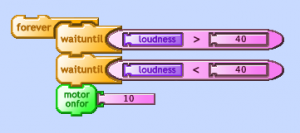

A motorized car was quickly enhanced by the ability to make it GO and STOP by making a loud noise. One or two sessions of adjusting the sensor tolerance to account for ambient noise and the toy car would stop and start on command! Friction, gearing and stable construction techniques were encountered along the way. Some of the programming needed my help because the software runs much quicker than a loud sound.

After joyfully sharing his invention with anyone he could find, the student had an original new idea!

He changed his computer program so that when a loud noise, such as a clap, was detected, the car would travel forward for exactly one second.

I was busy working with other groups of students and was unaware of the new direction for his project until I saw him lay a meter stick on the ground and grab a clipboard, pen and paper. He decided to measure how far the vehicle traveled (on that surface) in one second.

The kid knew that an average of multiple trials were necessary to ensure accuracy, so he got his TI-15 calculator. I suggested a strip of tape as a starting line and the experiment was underway. After multiple trials, the kid went to average the data and realized that he made a calculation error – without any intervention from a teacher or peer. He tried again and declared, “On average, the car travels 31 inches per second.”

Obviously, the next thing a kid wants to know is how fast the car travels in miles per hour (or kilometers per hour in nations using that silly metric system). Traditionally, this is the point at which all of the fun descends into math class hell.

How many seconds in a minute? How many inches in a foot? Yard? Mile? Seconds in a mile…” Ahhhhhhhhhhh!

That’s when I made my greatest contribution to the learning adventure. I whipped out my laptop, pointed my browser at www.wolframalpha.com and typed 31 inches per second into the calculation field.

A fraction of a second later, the handy web site told us that the car travels an average of 1.76 miles per hour. Not only that, but it provided context by telling us that the average human walks 2.5 miles per hour. Imagine that? Mathematical context!

When simple things, even repetitive calculations, are easy to do, complex things become possible. The student might decide to build a faster or slower car. He might challenge classmates to a robot race or see who can build a vehicle that will climb the steepest incline. These are all invitations to learn about force, speed, mechanical advantage, gear ratios and more. Or the kid may be content with what he has accomplished and embark upon a new learning adventure.

Lessons

- The project idea belonged to the learner. Occasionally I would ask a question or make a suggestion that would lead to greater experimentation.

- There was no scripted plan or backward design intended to get a kid from point-A to point-B. He achieved his objectives and learned more deeply along the way.

- That new knowledge and expertise is an asset to peers who want to try similar experiments or just integrate this kid’s ideas into their future projects.

- There was no formal show and tell. Kids collaborate and learn from each other naturally when the conditions value freedom, sharing, giddiness, whimsy and movement.

- There is no need to require every student or team of students to reproduce this project now or next year.

- There is almost never a time when more than 2-3 minutes of instruction is necessary before the students do something. If you are engaged in too much full-frontal teaching or whole-class instruction, try lecturing for half as long and shave a bit of time off each day until you get to less us and more them!

- Learning is natural.

- Learning is personal.

- Learning is a consequence of experience.

- Learning takes time, but not as long as it takes to “teach” the same lesson.

- Less is more.

- Kids should be allowed to be themselves and learn in a style that best suits them and a specific task. It is not up to the teacher to determine that comfortable style. Learning styles tend to be a lot more fluid and less confining than even well-meaning teachers believe.

- If you make simple things easy to do, you make complex things possible.

- Computers amplify human potential.

- Computing is the game-changer, not information access or ICT.

- A good prompt is worth 1,000 words!

- Curriculum was unnecessary.

- Teacher expertise and fluency with the materials, based on extensive personal use and experience are critical!

Want more information?

- Attend Constructing Modern Knowledge 2012

- Read 3 articles about effective project-based learning by Gary Stager

- Read Less Us, More Them – Creating learner-centered contexts for learning

- Read This is What Learning Looks Like

- Tinkering resources

- Seymour Papert’s Eight Big Ideas Behind Constructionism

- A Constructionism Primer

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.

That sounds freaking awesome! And I’m super jealous of your consulting job! Thanks for sharing. It gives me confidence to constructively argue with administration when wanting to introduce cool projects without a detailed plan (even though I know the project inside-out, like messing with Google Earth, or SketchUp, etc.).

It sounds exactly as I would want my own child (or myself) to learn. I can, however, hear the parent or fellow teacher saying something like “that’s great–we’ll do it AFTER the standardized testing” The other piece that I don’t believe you have addressed is the previous curriculum that has developed, on some level, knowledge that the students have used and built on in this project.

Gary,

Genuinely interested in why you think your greatest contribution to the learning was to provide a website that gave the child an answer to his inquiry?

What do you think he learned from that interaction? What did he want to learn? How did you assist his own learning at that moment?

Finally, while the concepts are evident through your explanation of the activity, how can you know, or assure the reader that the child engaged with those concepts and learned something about them as a result of his enquiry?

Please don’t misunderstand my intention here, I believe in the notions you propose, I’m not convinced by the description however that the learning you proposed could happen actually did happen?

Would love to hear more about it.

Cheers Vicki

Vicki,

Thanks for reading and commenting. I’ll address your questions one at a time.

WolframAlpha did not provide an answer to the kid’s inquiry, not that I’m sure that would be a bad thing. All it did was perform a calculation to convert units based on HIS experimental findings. That might lead to further deeper questions, such as, “Can I make my car faster? or “Can I make this faster than the average human walks?” The extra bit of info comparing the unit conversion with human locomotion was a delightful bonus.

As for “knowing” what the student learned, I have a good sense of that by working with and alongside of him. That gives me much greater insight into his thinking or understanding than a test would.

More importantly, the knowledge is demonstrated and manifest in the work that he did – the thing he built. There is no B+ or grade of 89, There is a persistance of reality that pushes back and your invention either works or doesn’t.

You may also be operating under the assumption that one particular powerful idea or curricular topic is more important than another, or experienced in a sequential fashion. Since I held no preconceived notions about exactly what each kid would learn during the activity. I could pay acute attention to what they DID learn and provide the ongoing support (through tips, conversation, deliberate materials) necessary to learn more.

I hope that answers your questions!

Gary

Gary,

I have followed your blog posts, other writings/presentations, and your ‘tweets’ for quite some time. I am often impressed by your rich examples of what you have done and what can be done with all ages and types of learners. I would have loved for my children to have been influenced by the type of educational environment you espouse. I would have loved to have experienced it as a learner.

The ‘sticking’ point for me always comes back to how this type of education could be done on a larger scale or ‘systematized’ in some way (by that, I mean what the structure of a school system would look like; how would students progress through the system; how would teachers be assigned and used, etc.). I also struggle with imagining the teachers I have worked with understanding how to work in this type of environment (I would say many could not) – and if those who are currently teaching do not have the skills now to do so, could they learn?

I have been spending quite a bit of time trying to figure out what education (K – 12ish) could look like in our country – and would love to be involved in genuine efforts to create something more like what you describe. I just have NO idea how to go about doing that! I would love to hear your thoughts on what steps could/should be taken or how people who are so inclined could become involved in that type of work.

In the meantime, I enjoy eavesdropping on the ‘lively debate’ your thoughts/comments often create!

Hi Sue,

In short, I think we need to dramatically raise our expectations for teachers while teachers themselves need a vocabulary for justifying their pedagogical choices in a coherent fashion.

We could help 100,000 teachers teach in this way over a decade, if we decided to do so. That would certainly have an impact on “the system.”

A wise old colleague of mine used to say, “I have no idea how to change a system. I know how to make one school better.” Rather than be overwhelmed by the daunting task of “changing the system,” why not begin by making the school day better for one kid?

You can certainly extrapolate, amplify and replicate lessons from the story I tell here, but at its core it is about one kid learning.

In your upcoming book (;0)) I would love for you to delve more deeply into what the paramaters of game-changing computing are. Are we good with computers but no online access? Does access expand any of the game-changiness of computers? (I mean you didn’t really NEED Wolfram Alpha in the above example.) Could (and if yes, should) we create game-changer learning activities that extend beyond the walls?

I’ll be waiting to read…

Gary,

I enjoyed this post and it reminded me of something I think is similar in the core idea of student learning. http://www.danpink.com/archives/2011/05/what-your-business-can-learn-from-a-6th-grade-classroom

You hit a number of key ideas in the list of lessons at the end and I will certainly be sharing this experience with others. It always amazes me in the face of all the research about individualized learning that we still try to put it in boxes and create curricula for all.

Hi Will,

You are quite correct, I did not need Wolfram Alpha, but it did provide a delightful bit of serendipity and kept the activity from getting bogging down with tedious calculations that may have derailed the activity, robbed it of its spirit or consumed precious time.

The game changiness is in the fact that the computer granted agency to a kid to engage in authentic engineering activities. The computer moderates a conversation with one’s self. If you’re hypothesis is successful, you embellish, test a larger hypothesis or issue yourself a more complex challenge. If you are unsuccessful, you engage in some debugging processes.

Debugging used to be the primary justification used for why computers belonged in education. You confront problems which may be solved in multiple ways that you need to identify, refine and test. there are few contexts outside of programming that provide such fertile opportunities for debugging.

Where I might disagree with you is on “depth-of-field” (don’t know if that metaphor works). I do not believe that there is anything inherently better about a learning experience that happens “out there” (on the network). Although, there are certainly fine opportunities to learn “out there,” all learning truly occurs within the learner. (OK, Stager – that was effing profound if I do say so myself)

My new book is not about technology.

Ok. So if I read you correctly, since all learning truly occurs within the learner, and since the computer moderates a conversation with one’s self, there really is no need for any social interaction in a learning context. The scenario you offer above could have been just as successful for the individual learner if it had occurred with no one else around. Would that be accurate?

Apologies about my future book ignorance.

Will,

There was a great deal of social interaction taking place in the scenario I described – between the teacher and learner and between students. There is collaboration even when students don’t work together as an idea, discovery or technique spreads through the learning environment. My colleague, Yasmin Kafai used to call it “collaboration through the air.”

However, much of that social interaction was quick, casual or tacit. It was not in the form of discussion, reading or writing – the modalities commonly thought of as social interaction.

I was looking for something clever to say about my forthcoming book. I fell short of that goal.

Thanks. So, not to belabor this, but then back to my original question which I’m not sure you really answered:

Could (and if yes, should) we create game-changer learning activities that extend beyond the walls?

Will,

Of course we can.

However, I’m not sure that is one of my priorities. It might be for other people.

I just don’t think there is anything inherently better about the cloud than face-to-face. Both have affordances and constraints. I’ve written and spoken about that quite a bit.

I am not against being online or learning online. Some biographical context:

I’ve been online for about 30 years and have taught online for half of that. The first online “unconference” i participated in was in 1985 or 1986. I led collaborative online projects with students in the Scarsdale, NY public schools in 1989. I taught with the National Geographic Kid’s Network science projects in my 4th grade class in 1990.

Thanks.

Just for clarification, I think the story you tell here is amazing, and it articulates a model of learning that I want for my own kids. They’re not getting anything close to this in schools, and I think it already has and will have deleterious long term effects on their development as learners. I already regret many things about their “education” and my role as a parent in it. I’m not worthy.

Further, I’m not claiming that there is “anything inherently better about the cloud than face-to-face.” What I am claiming is that to ignore the “affordances and constraints” of the cloud or the network because it changes the interaction is equally as deleterious to our kids’ learning in many ways. My thinking around “bold schools” leads me to see them as places where all of your 18 lessons above are embraced as well as lessons #19 (learning is networked), #20 (sharing with a global audience enhances the opportunities to learn more), #21 (learning can have real world application and reach), and probably a half a dozen others. I just don’t think we can do one without the other any longer.

As always, I appreciate your willingness to engage and push. We agree much more than we disagree, and it’s always good to test my passions.

Gary,

Thanks for the response. Although I agree it would be a worthy endeavor to make the school day better for one kid (I imagine I could have done that for 2 kids had I chosen to home school my own) or even one school (if one actually had the authority and support to do so). Those of us who must rely on working FOR and WITHIN a system (a public school system), though, are not afforded such liberties.

Could I, as teacher do SOME of what you describe? Yes, I believe I could (and did on some level when I taught mathematics) – though not quite so drastically. I was limited significantly by the ‘curriculum’ and by what parents and others expected children to be “learning.” I have always had to balance doing what I believed with keeping my job – not an easy thing to do.

I believe the dilemma and challenge is that doing something for 1 child or one school sounds noble and good, but t is not enough to make sustainable & long-lasting change in the way we educate – and that is what is desperately needed. Someone(s) need to find a way to turn a philosophical approach into a greater movement – or at least find a way to gather people with a similar philosophy and belief together and find a way for them to make a living by working with kids in the way you describe. The sad fact is – most of us need to earn a living by going to a job every day and I think most of do the best we can in staying true to our core values when we go to that job – even when those core values are not completely aligned with the system in which we work. Yet, there are tens of thousands of kids who are ‘trapped’ in those systems with us.

I know there are schools that have been started by people like Deborah Meier and Dennis Litky – even Maria Montessori – and I wish I could start one – or work in one. I have had a number of very talented teachers who have asked me to start one so they could come and work in it. But wishing and hoping is not a great strategy; I guess I need to keep exploring how to make that a reality! If I do, I’ll see if you’re available to provide support for the teachers!

Thanks Gary,

As I said in my first post don’t get me wrong I’m a believer in the activity/enquiry proposed.

I ask the questions to help understand your perspective and perhaps illuminate the depth of thinking, interaction and learning that comes from quality social interaction and engaged inquiry.

I think it’s important to capture these points as practitioners need to think about the experience you presented with an understanding of why rather than simply what.

I’m not particularly interested in curriculum topics or subjects at all, I’m interested in learning and how it can be personalized………but an activity/project/enquiry does not mean learning takes place……you gave an example of this in your recent post.

So Thankyou for your answers, they explain your thinking further and have helped me get a better understanding of your perceptions in relation to the students learning and your role as facilitator.

Looking forward to reading more about your ideas

Vicki

No problem, Vicki. There is no need to qualify your questions.

Thanks for reading,

Gary

I’m having troubles parsing your contra “anarchy” paragraph. Did you mean “*and* even believe…”?

Gary,

Thanks so much for the invitation to participate in this conversation. One of the many things that hit home for me was something that has come out of many of my workshops and presentations over the last few months. It’s the rise of a different kind of assessment, one that’s quite old, but also quite new within the current context of “teaching kids.” The message of this assessment is not, “You got that right (√)” or “You got that wrong (X)!” The message is, “That worked!” Or “That didn’t work!” ..and regardless of the response, the learner walks away with a new piece of knowledge.

I taught history, and I couldn’t have told you this at the time, but I always taught history from the perspective of how various newly invented technologies affected cultures. It’s the main reason I was so profoundly affected by the first personal computer I operated (Radio Shack Model I). I knew in my bones that this was going to be one of those technologies that was going to profoundly change us.

But what occurred to me, while I was reading your blog post and the subsequent conversation was, “What if I had been teaching history to students who were, themselves, inventors? Might it have altered my own pedagogies if I had been helping learners to build and evaluate historical contexts, and they were approaching it as accomplished inventors and builders? What might I start watching them build in my history classes? What might my history classes evolve into as they become so tied to science, mathematics, music, art, health…? What might that school become?

It reminds me of a teacher friend of mine in New Brunswick Canada, who was ready to start his unit on government and politics. Rather than simply teach the unit as he had for years, he asked student teams to devise a political party, flesh it out with a platform of positions, imagine a candidate, write campaign speeches, hold an election, and all along the way, talk about what they were doing, critique the activities of others, and defend their learning.

If “all learning truly occurs within the learner” (and I agree, that’s a pretty darn profound revelation), then isn’t learning, in a way, a form of self-invention?

How different is that from teaching as a form of standards-driven mass production?

Hi David,

Thanks so much for taking the time to read and respond.

I don’t wish to rain on your parade, but is it possible that the “progress” you cite in terms of assessment might be relegated to the sorts of schools that hire us and yearn to be better/different? It’s understandable in these times to search for any semblance of a silver lining.

I also don’t know if “that works” or “that doesn’t work.” Is much more information than “right” or “wrong.”

Teaching is undoubtedly made more powerful through storytelling, simulation, re-enactment, connection-making, etc… This is can be traced to the ancient Greeks, and probably to cavemen.

In preparation for the 1980 Presidential election, my entire high school ran a Presidential primary, complete with candidates, position statements, speeches, debates and campaigning culminating months later with a gym-filled day-long nominating convention complete with balloons, signs, costumes, etc…. The school had done this every election cycle for decades..

Perhaps I’m too optimistic, but I view such teaching activities as self-evident and the least we should be doing, especially given the remarkable potential of computing and unprecedented access to information.

I don’t think that suggesting that learning occurs within the learner is all that profound a proposal. However, two of the ideas behind this post are indeed quite radical.

1) The content you’re teaching doesn’t matter nearly as much as what the children are learning. If kids spend between 14,000 and 16,000 hours in school, they ought to learn all sorts of things society values – and then some.

2) Teachers need LOTS of expertise, knowledge, skill and experience. It’s time to stop minimizing this point (see #18). I can teach this way, not only because I don’t care about a lot of the silly things teachers are told to care about AND because I have spent thousands of hours programming, doing engineering projects with kids, reading, going to concerts, attending conferences, traveling, visiting museums, apprenticing with experts and I’m curious.

That does NOT make me a “magic” teacher who can’t be “scaled” or replicated. Such thinking is a capitulation to the status quo. I expect that every teacher can lead a deeper richer life and share those experiences explicitly and tacitly with children.

If you wanted to learn to build good houses, you would spend lots of time with great carpenters. If we want kids to be good learners, they should be spending school time with great learners.

I will write something about teaching history specifically in another comment.

Thanks so much for contributing to this discussion. I appreciate it.

Best,

Gary

I have had similar experiences in teaching science, history, and even reading. I also usually find that different students break through somehow and make the experience their own (usually through changing the outcome they are looking for in some way.) For example, student A runs with today’s science lab while student B extends the history assignment.

My problem is that even though many of the students throughout the year grab hold of something, I still have some that never find their “thing”. I suspect that the narrowness of the curriculum combined with the over-emphasis on testable facts alienates these students. Last year I had a student that could not read at grade level (honestly he wasn’t close to grade level). He knew he wanted to be a mechanic after high school. I am sure you are not surprised that he had no opportunities in school (at least in our junior high) to pursue this goal. Actually, he is a lucky one because he can take classes in high school that move him towards his goal.

I completely agree that learning takes place internally, but I believe that is our (the school, community, nation, world) responsibility to create opportunities for students to learn. If we can’t or won’t do that, the kids will have to find ways to learn what they want without us (which I believe many are doing). For too many, learning is what takes place outside of school because they are doing what they want to do.

So, we created a lesson that completely engaged one student. Now what do we do with the other student that is completely disengaged? Is it enough that one excelled?

Gary, why would I respond if I didn’t want the rain 😉

I believe that you sell my distinction about assessment way to short, though it’s probably because I didn’t make myself clear enough.

“Assessment” has come to mean something that is way to limiting for our own good. Summative and even formative assessment are performed for the benefit of the teacher, measuring the success of instruction. I know I’m being way to simplistic, but I only want to spend a few of your lines.

The assessment that I’m trying to describe does not measure the learning outcome, it is part of the learning process. Pedagogically, it implies a learning experience that goes much deeper than merely being presented with knowledge. It involves a learner working/playing the information with developing skills (and tools) to construct new knowledge and perhaps to construct value.

I suspect, from my own experience, that the most explicit example of this is programming. I know I’ve got it, because it worked. Then I can take what I’ve got, and do new things with it. Sometimes I can take what didn’t work, and do new things with that.

I remember the afternoon of my first programming experience, getting down on my knees and mentally yelling to all my former Algebra teachers, “I finally understand what you were trying to teach me!”

But back to history, in 1992, teachers across the state of North Carolina participated in a project that we called “VoteLine” (http://goo.gl/vehEc). We (North Carolina Department of Public Instruction – NCDPI) provided each class with AppleWorks spreadsheet and database templates and a set of suggested activities (http://goo.gl/AiJp9).

Essentially, students reviewed news coverage to identify the major issues of the election(s). Then they investigated the campaigns for the candidates’ positions (Bill Clinton’s speeches were available via FTP and Gopher and shared among teachers using FrEdMail) and surveyed their community to learn local feelings about the issues. They also drew conclusions from demographics databases about the likely opinions of NC citizens.

Students, working in teams, then added the issues to the spreadsheet, weighting each based on the candidates’ positions, public opinions and demographics — and the spreadsheet calculated a projected outcome.

We (NCDPI) provided fictitious scenarios — what if this were to happen, how do you think that might effect the outcome, or how would you advise your candidate to react?

Bottom line is that it didn’t work, because Jesse Helms should have been soundly defeated. But new questions were asked by students, “What did we not factor in?”

Weeks later, during the debriefing with teachers, a number of them explained how they knew “it worked,” when they noticed students, in the halls at their lockers, continuing the discussions they’d been having in class — a very fine assessment in my humble opinion.

I think there is an important distinction between a teacher saying “that doesn’t work” and a project not working. The project not working is reality – the program isn’t running, the cake doesn’t rise, the egg dropped from the roof breaks, etc. The broken egg is feedback; the teacher saying “this doesn’t work” is assessment and not that different from saying “that’s wrong”. If the student has to look to the teacher to tell them if something is working, there’s a problem.

This is obviously not a call for teachers to remain silent, but to design projects where the success or failure is a natural outcome of the project, and something the learner could possibly have a say in, not an external goal imposed by the teacher.

I was more than happy to find this net-site.I needed to thanks in your time for this excellent read!! I undoubtedly enjoying each little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to take a look at new stuff you blog post.

Is the debate about what is the purpose of education? Is it to create skills sets around content? Is it to develop skills around problem solving ability or critical or creative thinking? It is to develop skills in our ability to communicate? Is it to provide opportunity to enhance and build capacity to transfer skills and abilities of a multitude of learning?

It’s not about …? curriculum? learning environment?

Everyone’s comments about Gary’s example of a project to help think deeply about learning environments, were very enlightening. As I would not put myself in the position of an educational expert as many of the commenters are, I would like to offer the above wondering I have about the post.

you could have an excellent weblog right here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?

I agree with your point “Computers amplify human potential.”. I believe that having the student use Wofram Alpha to convert units (rather than spending hours of class time and cognitive capacity learning this skill which can be easily done by a computer) so that he could focus on his project and exploring other possibilities nicely illustrates the way humans should partner with computers. Offloading cognitive load to devices frees students up to hone their ability to create, problem solve, and interact.