The debate about technology’s place in classrooms might vanish if the machines are used to expand students’ self-expression

Be sure to read to bottom!

![]()

A version of this column appeared in the March 2001 issue of Curriculum Administrator Magazine.

I recently attended attended Apple Computer CEO Steve Job’s keynote address at the annual Macworld Conference in San Francisco. Amidst the demonstrations of OS X, the launch of the sexy new Titanium Powerbook and the obligatory race between a Pentium IV and Macintosh G4 (you can guess which won), Jobs said some things that I believe will be critically important to the future of computing.

Quotations from the CEOs of Gateway and Compaq decrying the death of the personal computer were rebuffed by Jobs who not only asserted that the PC is not dead, but that we are entering a new age of enlightenment. Steve Jobs declared that the personal computer is now “the digital hub for the digital lifestyle.”

While everyone is excited about new handheld organizers, video cameras, cell phones and MP3 players, these devices not only require a personal computer for installing software, backing up files and downloading media – they are made more powerful by the PC. The personal computer is the only electronic device (at least for the foreseeable future) capable of multimedia playback, supercomputer-speed calculations and massive data storage. Most importantly, the personal computer is required for those who wish to create, rather than be passive recipients of bits generated by others.

Jobs discussed how video cameras are cool, but iMovie makes them much more powerful. Boxes full of videotapes are no longer lost in the attic, because you can easily produce edited movies shareable with friends, relatives and the world. Jobs then launched iDVD, Apple’s stunning new technical breakthrough that allows anyone to create their own DVDs in minutes. Think about what this could mean in a classroom! Class plays, science experiments and sporting events could be shared with the community and playable with state-of-the-art quality on the home television. Video case studies of best practice can be used in teacher education complete with digital quality audio/video. Zillions of digital photos and scanned images of student work can be assembled as portfolios stored on one disk and viewed anywhere.

A company representative from Alias Wavefront was brought to the stage to demonstrate their software package, Maya. Maya is the 3D graphics tool used by George Lucas to make the most recent Star Wars film and by all of last year’s Oscar nominees for best special effects to work their artistic magic. The quick demo showed how a flower paintbrush could be chosen and with the wave of the mouse flowers could be drawn in 3D on the computer screen. These were no ordinary flowers though. The software knew to make each flower slightly different from the others, as they would appear in nature. The software also knew how they would behave if wind were to be added to the scene. Clouds drawn knew to move behind the mountains. Until now, Maya required a specially configured graphics workstation. It now runs on a Macintosh G4. While the software is currently too expensive for most kindergarten classrooms, it occurred to me that the world will be a much cooler place when five year-olds can use Kid-Pix-level fluency to create with the same tools as George Lucas. Perhaps then they will stop blowing up their Kid-Pix creations and express themselves through film.

Jobs argued that iMovie makes video cameras more powerful and iDVD enhances the value of both the video camera and DVD player. Therefore, the personal computer not only powers digital devices, but empowers our lives. This is a profoundly liberating and enabling vision for society.

As I left the auditorium I thought, “Steve Jobs really gets it!” However my admiration for his vision and desire for the new “toys” was quickly tempered by thoughts regarding the imagination gap guiding the use of computers in schools. Not once did Jobs compare the PC to the pencil or refer to it as a tool for getting work done. No standards for computer-use were offered. Instead, he challenged us to view the computer as a way of inspiring a renaissance of human potential.

Just Make Something

The personal computer is the most powerful, expressive and flexible instrument ever invented. It has transformed nearly every aspect of society, yet schools remain relatively untouched. Rather than be led by technological advances to rethink models of schooling, schools and the software industry have chosen to use computers to drill for multiple-choice tests, play games and find answers to questions available in reference books via the Internet. While the Internet is an incredibly powerful and handy reference tool, it’s real potential lies in its ability to democratize publishing and offer unprecedented opportunities for collaboration and communication. The dominant practice is to restrict or forbid this openness through filtering software, acceptable-use policies and overzealous network administrators. When the paradigm for Internet use is “looking stuff up” it should come as no surprise that kids are going to look at inappropriate content.

The results of this imagination paralysis are too numerous to mention. The hysteria over Internet use, growing disenchantment with schooling and calls to reduce tech funding are clearly the consequences of our inability to create more explicit, creative and public models of computers being used by children to learn in magnificent ways. The recent dubious report, Fool’s Gold, by the Alliance for Childhood, takes aim at school computer-use by illustrating the trivial and thoughtless ways computers are used in schools. A moment of candor requires us to admit that most of their criticisms are valid. Schools do use computers in dopey ways. However, that is not a legitimate argument for depriving kids of the opportunity to learn and express themselves with computers. It is however an indictment of the narrow ways in which schools use technolology. Experts advocating the use of handheld devices as “the perfect K-12 computer” so that students may take notes or have homework assignments beamed to them are cheating our young people out of rich learning adventures.

It’as if schools have forgotten what computers do best. Computers are best at making things – all sorts of things. Educational philosophers including Dewey, Piaget, Papert, Vygotsky, Gardner have been telling us forever that the best way to learn is through the act of making things, concrete and abstract. The PC is an unparalleled intellectual laboratory and vehicle for self-expression yet schools seem ill-equipped or disinclined to seize that potential.

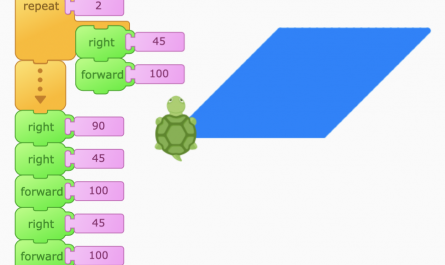

Kids can now express their ideas through film-making, web broadcasting, MIDI-based music composition and synchronous communication. They can construct powerful ideas (even those desired by the curriculum) through robotics, simulation design and computer programming.

While there is much rhetoric about kids making things with computers, those projects tend to reinforce old notions of teaching. Hyperstudio book reports or databases containing the pets owned by classmates are not what I have in mind. Kids should make authentic things borne of their curiosity, interests and reflecting the world in which they live.

I cannot imagine that the critics of public education and the investment in educational technology would object to kids using computers in such authentic, deeply intellectual and creative ways. Rather than creating unproductive standards for computer use, educational computing organizations should be building, documenting and sharing compelling models of how computers may be used to inspire joyful learning throughout the land.

Seymour Papert has proposed that we “view the computer as material.” This material may be used in countless wonderful and often unpredictable ways. Teachers are naturally gifted with materials of all sorts and the computer should be part of that mix. This change in focus should reap rewards for years to come.

We can do good and do well by exercising a bit more creativity. We can neutralize our critics and move education forward if we shift our focus towards using school computers for the purpose of constructing knowledge through the explicit act of making things. Children engaged in thoughtful projects might impress citizens desperate for academic rigor. Emphasizing the use of computers to make things will make life easier for teachers, more exciting for learners and lead schools into this golden age. [Emphasis 2016]

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.