The irony could cause whiplash. Over the past thirty years, the EdTech community expended sufficient energy to colonize Mars fighting the idea of teaching children to program computers. I cannot think of another single example in education where so much effort was invested in arguing against children learning something, especially ways of knowing and thinking so germane to navigating their world. Now, the very same folks responsible for enforced ignorance, disempowerment, and making computing so unattractive to children are now advocating “Computer Science for All.”*

There seems to be little consensus on what CS4All means, few educators prepared to teach it, no space in the schedule for a new course of study, and yet a seemingly unanimous desire to make binary, algorithm, and compression first grade spelling words. The sudden interest in “coding” is as interested in the Logo community’s fifty years of accumulated wisdom as Kylie Jenner is interested in taking Ed Asner to St. Barts.

So, amidst this morass of confusion, turf battles, and political posturing, well intentioned educators resort to puzzles, games, and vocabulary exercises for say, an hour of code.

I wish I had 0101 cents for every educator who has told me that her students “do a little Scratch.” I always want to respond, “Call me when your students have done a lot of Scratch.” Coding isn’t breaking a code like when you drunken insurance salesman go to an Escape Room as a liver bonding exercise. The epistemological benefit of programming computers comes from long intense thinking, communicating your hypotheses to the computer, and then either debugging or embellishment (adding features, seeking greater efficiency, decorating, testing a larger hypothesis).

Fluency should be the goal. Kids should be able to think, write, paint, compose, and dance with code. I recently met a team of sixth grade girls who won a contest for creating the “best app.” It was pretty good. I asked, “What else have you programmed?” and received blank stares. When I asked, “What would you like to program next?” the children all turned to look at the teacher for the correct answer. If the kids were truly learning to program, they would be full of independent ideas for what to do next.

Children have a remarkable capacity for intensity and computer programming is an intellectual and creative outlet for that intensity. When I learned to program in a public middle school in 1975, I felt smart for the first time in my life. I could look at problems from multiple angles. I could test strategies in my head. I could spend days thinking of little more than how to quash a bug in my program. I fell in love with the hard fun of thinking. I developed habits of mind that have served me for more than four decades.

So, for schools without a Mr. Jones to teach a nine-week mandatory daily computer programming class for every seventh grader, I have a modest proposal that satisfies many curricular objectives at once.

Whether your goal is literacy, new literacy, computer literacy, media literacy, coding, or the latest vulgarity, close reading, my bold suggestion offers a little something for everyone on your administrative Xmas list.

Give the kids a book to read!

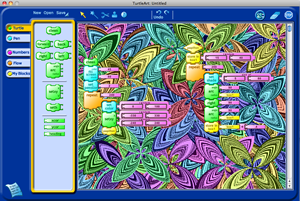

That’s right. There are two very good books that teach children to program in Scratch using a project-approach. The books are completely accessible for a fifth grader. (or older) Here’s what you do.

- Buy a copy of one of the recommended books for each student or pair of students.

- Use the book as a replacement text.

- Ask the students to work through all of the projects in the book.

- Encourage kids to support one another; perhaps suggest that they “ask three before me.”

- Celebrate students who take a project idea and make it their own or spend time “messing about” with a programming concept in a different context.

There is no need for comprehension quizzes, tests, or vocabulary practice since what the students read and understand should be evident in their programming. Kids read a book. Kids create. Kids learn to program.

There is a growing library of Scratch books being published, but these are the four I recommend. The first two choices may be the best since they were specifically written for the current generation of Scratch, Scratch 3.

25 Scratch 3 Games for Kids: A Playful Guide to Coding by Max Wainewright is a beautiful new book of Scratch 3 game programming projects presented in a highly visual style. (grades 4-7)

Super Scratch Programming Adventure!: Learn to Program by Making Cool Games is a terrific graphic novel filled with Scratch projects. (grades 4-7)

Scratch For Kids For Dummies by Derek Breen is a terrific project-based approach to learning Scratch. Note: This was written for Scratch 2.0, but remains a valuable resource, particularly for teachers.

If per chance, thick books scare you, there are two excerpted versions of Derek Breen’s Scratch for Kids for Dummies book, entitled Designing Digital Games: Create Games with Scratch! (Dummies Junior) and Creating Digital Animations: Animate Stories with Scratch! (Dummies Junior). Either would also do the trick. Note: These were written for Scratch 2.0, but remain useful.

Growth

I must admit to being alarmed by the frequency with which many educators tell me that their students “Do a little Scratch.” Scratch and “Hour-of-Code” type activities present an illusion of simplicity that is misleading. Fluency only develops from doing “a lot of Scratch.” The emergence of “advanced” Scratch programming books provides evidence of growth in the community and enhances the sustainability of the programming language.

Another Must-Have

Natalie Rusk’s terrific The Official Scratch Coding Cards (Scratch 3.0): Creative Coding Activities for Kids are a must-have for any Scratch-using classroom.

You might also enjoy:

- The Invent To Learn Guide to Block Programming.

- New programming environments for learning (Fall 2020)

Shameless plug

Sylvia Martinez and I wrote a chapter in the recent book, Creating the Coding Generation in Primary Schools.

* There are a plethora of reasons why I believe that Computer Science for All is doomed as a systemic innovation, but I will save those for another article.

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.