I have often wondered why educators are so darn excited about Google. They get “Google Certified,” attend Google conference sessions, mourn when features change or Google loses interest in a platform they LOVE(d). Google loving teachers attend summits that are a cross between an Amway convention and cult meeting. Districts trust their communications and document storage to a company they know harvests their data (and that of their students) just to save a few bucks on an email server. School leaders have never met Mr. Google or any of his designees, but trust them anyway.

Millions upon millions upon millions of dollars are spent annually on teaching seemingly competent adult educators to in the words of President George W. Bush, “use the Google.”

Now, don’t get me wrong. The Google is a swell thing. You type something into a box and related web pages are displayed – just like the search engines that came before it. Google PhotoScan is a little piece of magic for rescuing and preserving family photos. We trust Google a lot and have become reliant on a faceless corporation who can change the terms of service or kill a platform we rely on at the drop of a hat.

One of my favorite tweets of all time was when I asked, “Which should I care less about, Google Wave or Google Buzz?” It turns out that I hit the exacta when Google quickly took both Wave and Buzz behind the barn and shot them Gangnam Style. I get the sense that Google operates like libertarian toddlers who just finished a jumbo box of Lucky Charms cereal right before their community theatre performance of [easyazon_link identifier=”0399501487″ locale=”US” tag=”neweasyazon-20″]Lord of the Flies[/easyazon_link].

Mad at me yet? No? OK. Good. Let’s move on.

The one Google thingy that schools really love is Google Docs. Boy, do they love Google Docs.

I have long wondered why? We have had word processors for thirty-five years. Most computers come with a free one adequate for most school applications and there are certainly better “Office” suites available. Many schools already own them.

So, why oh why the love affair with Google Docs? I offer a few hypotheses.

Here are the Top Three Reasons Why Schools Love Google Docs. [Drum roll please…]

- Google is cool. The Googleplex has vegan cafeterias, free dry cleaning, massage chairs, AND Ping-Pong tables. I wish our teacher’s lounge had a Pachinko machine and an assortment of herbal teas. That would make me cool too!

- Nuthin’ cheaper than free

and the number one answer why schools love Google Docs is….

- Collaboration!!!!!!

Collaboration is nice. Schools like nice. Being collaborative is what nice people do when they want to create nice things.

We have been here before

In the late 1980s, collaboration was all of the rage, but back then it was called cooperative learning. Cooperative learning. A school district sent me to a Robert Slavin Cooperative Learning Boot Camp run by Johns Hopkins University. Like any good boot camp, its intent was to beat us down and build us back up again as champions of cooperative learning. Colleagues were immediately separated so they could not question the dogma or rebel in any way. We learned to “jigsaw” boring and irrelevant curricula.

We were taught to create student teams of four kids; always four kids. The teams should be comprised of a smart kid, a dumb kid, a girl, a boy, a Black kid, a White kid, a skinny kid, a fat kid… Each team should stay together with their desks side-by-side for six weeks, always six weeks. If we did this, spelling test scores would improve.

Of course, during that prehistoric era, Google engineers were not even old enough to disrupt their own Waldorf schools. So, sadly there were no Google Docs to create multiplication flash cards or use all of our vocabulary words in a sentence. The word-processed five-paragraph essay in the cloud would have to wait.

TRIGGER WARNING!

Since 90% of what schools do is Language Arts and 98% of what they do with computers is language arts[1], Google Docs is mostly used for writing, but its secret power is collaborative writing.

I am a professional writer. (Not that you can tell from this essay) I am the author of hundreds of magazine articles, about as many blog posts (yeah, big whoop), a 450,000 word doctoral dissertation, countless academic papers, and co-authored one of the best-selling books about educational technology.

All of this qualifies me to say something heretical. (IMHO)

Writing is not collaborative!

(Please take a deep breath before declaring me a big meanie poo-poo head.)

You may write different parts of something and smush them together. You may peer-edit. You may create an anthology or periodical containing writing by several people, but writing is a solo sport. Writing is the result of one person’s internal processes.

Collaboration is more than simply the division of labor. It should not be taught as an isolated skill or coerced. Sadly, like many seemingly good ideas, schools seek to mechanize collaboration by turning natural process into a set of measurable skills and multi-year course of study, easily assessed. Some children win, while others fail.

Teams are created by teachers drawing Popsicle sticks with kids’ names written on them (until the teacher doesn’t like a random pairing and “fixes” it.) Students sense the capricious nature of this process and waste precious class time working the refs to get assigned teammates they like. Working with people with whom you are compatible is a logical idea frequently squelched by school “collaboration.”

Back in the halcyon days of Cooperative Learning™, a reporter for the long-defunct Electronic Learning Magazine asked Seymour Papert an intentionally softball question, “What do you think of Cooperative Learning?” Papert replied, “I think it is a profoundly bad idea to force children to work together.”

Oooh! Snap!

Collaboration should be natural

Cooperation and collaboration are natural processes. Such skills are useful when the creative process benefits from interdependence. The best collaboration mirrors democracy when individual talents, knowledge, or experiences are contributed to produce something larger than the sum of its parts.

Work with your friends. Work with people you trust. Work with people who have different skills or expertise. If that doesn’t produce the result you desire, you will find others to collaborate with. That is how you learn to collaborate. You may teach it, but the students will not stay taught.

Honestly, I could not care less about whom my students (kids or adults) choose to work with. The only reason to assign group size is scarcity of materials (we have to share). Even in those largely avoidable scenarios, it hardly matters if group size varies a bit. The main consideration is inactivity by some members when a group is too large.

Collaboration is both selfish and selfless. You give of yourself by sharing your talent and expertise, but the collaboration should benefit you as well.

Collaboration should be fluid

One of the great joys of Constructing Modern Knowledge derives from the range of collaboration on display at my annual institute. At the start, participating educators suggest a vast array of project ideas ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous. Participants identify which project they wish to work on and commence collaboration. If a person loses interest, becomes inspired by another project, or is incompatible with a teammate, they are free to join a different project or start a new one. Some people move effortlessly between multiple project teams; learning even more.

When projects are shared at the end of four days, three to five person teams have created the majority of projects, some may have a dozen or more collaborators, and we often discover delightful projects created by someone who quietly sat in the corner and worked alone.

I have been fortunate to learn a great deal about what I know about learning from some of the world’s best jazz musicians. Those who are expert at what they do, like musicians, artists, and scientists, pursue greatness by working tirelessly on what bugs them. That continuous and indefinite attention to detail makes them incredibly good at articulating how it is that they do what they do. In other words, they are great teachers.

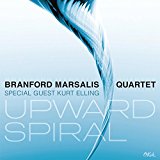

The very fine jazz pianist and educator Peter Martin recently interviewed saxophonist Branford Marsalis and vocalist Kurt Elling about their remarkable collaboration, “Upward Spiral” (recording and tour). Marsalis and Elling are both highly accomplished A-list artists with their own working bands and artistic concepts. Yet, they have decided to spend a couple of years putting “their thing” on hold to create something new, wondrous and collaborative in the best, most natural, sense of the word. The music they create together on stage is transcendent and not to be missed.

The very fine jazz pianist and educator Peter Martin recently interviewed saxophonist Branford Marsalis and vocalist Kurt Elling about their remarkable collaboration, “Upward Spiral” (recording and tour). Marsalis and Elling are both highly accomplished A-list artists with their own working bands and artistic concepts. Yet, they have decided to spend a couple of years putting “their thing” on hold to create something new, wondrous and collaborative in the best, most natural, sense of the word. The music they create together on stage is transcendent and not to be missed.

During Peter Martin’s podcast, my old friend Branford Marsalis shares his profound concept of collaboration and juxtaposes it against the version so often practiced in schools. There is much to be learned here.

“The whole idea of a collaboration (to me) is that nobody gets to do what is that they do. The modern interpretation of collaboration is I know what you do. You do know what I do. Let’s get a head start and run real fast and collide into one another and whatever spills out over the side is the collaboration.” – Branford Marsalis

True collaboration is great. It’s even better than a free word processor.

Notes:

[1] I pulled those figures out of my bum, but I have been doing so for decades and no one has been able to disprove this completely fabricated assertion.

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.