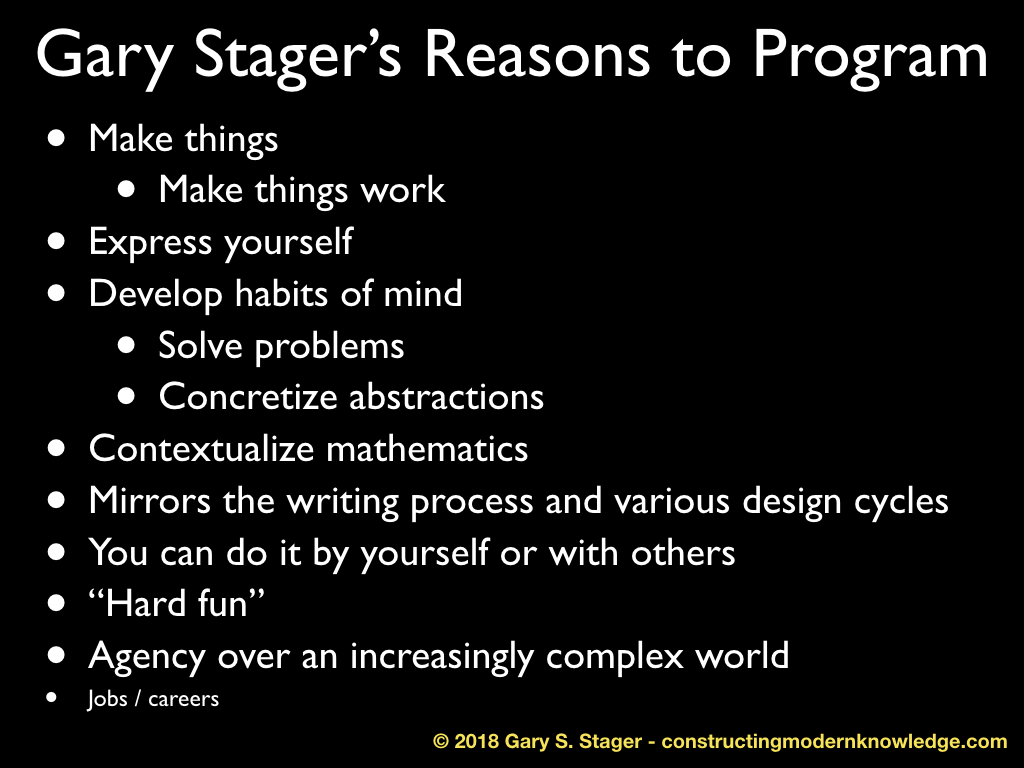

All children should learn to program, not because it may lead to a job, but because it is a new liberal art and grants young people agency over an increasingly and technologically sophisticated world. At a time of rising authoritarianism and science denialism, it seems prudent to provide kids with experiences that develop a systematic way of making sense of the world. It may literally be the least we can do.

Current approaches to teaching computing to kids suffer from the traditional failures of curriculum development and too often fall prey to the following desires:

- vocabulary acquisition

- a condescending view of teacher competence

- convenience

- frugality

- ignorance of the intellectual euphoria associated with bending a computer to your will

- offering students an illusion of agency without actual power

- speed

The calls for “CS for All” are right out of the timeless schooling playbook; require a new subject without a requisite investment of funds or imagination and reduce it the sort of lifeless content devoid of experience that is easily tested. For extra credit, “demonstrate” that some students just don’t have a facility for the subject. A bell curve would be swell, but the real goal is for the “new subject” to fail with only children and their teachers to blame.

There is no better way to explain the quality of computer science curricula being developed for school use. Much of this curriculum is designed by interns or the very same educators who presided over the death of interest in CS. In many cases, the curriculum focuses on isolated topics, rather than on doing. What can a student do with the information being taught? Fluency is the goal!

(IMHO) Computer programming is not a means to demonstrate understanding of computer science jargon or even a technical act. At its best, computer programming a form of composition – like writing, music composition, painting, sculpting, or dancing. A handful of carefully designed assignments does not make one a computer programmer any more than it produces authors, musicians, or artists.

Computer programming mediates a conversation between the person and herself. Skills and habits of mind emerge from acts of creation, development, and debugging. One might think about this in terms of the purest forms of project-based learning where the project is a teacher’s smallest unit of concern and students are free to lose themselves in the process of realizing something that matters to them.

Great expertise is developed by identifying things that bother you, a laser-like focus on overcoming that obstacle, and the emergence of a new thing that bothers to you as you approach your temporary goal. This phenomena maps perfectly to the process of programming and debugging. It also matches a young person’s remarkable capacity for intensity while mirroring the writing process and other forms of composition.

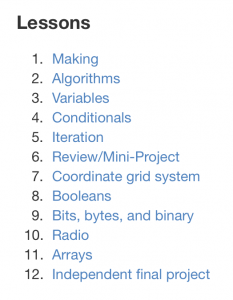

Show kids a primitive or two and see what they can do with it. The genius of “Logo family” languages, like MicroWorlds, Lynx, Scratch, Snap!, TurtleStitch, Beetleblocks, Turtle Art, or perhaps even MakeCode is that seemingly infinite world of complexity can be realized with a handful of commands or blocks. With forward and right, you can draw anything in the universe. New commands, reporters, variables, conditionals, and control structures may be introduced to students as they need them. Programming elegance results from constraints or experience. Since microcomputers are no longer limited to 4K of RAM, “efficient” code becomes less of a necessity and more of an aesthetic quality that develops over time.Allowing kids to program in their own voice allows them to concretize abstractions and solve problems while developing programming prowess.

The Piagetian adage, “knowledge is a consequence of experience,” is certainly true for programming. The more you program and the longer you stare at the screen of what you are programming, the better you will become at it. Schools that “or a little bit of Scratch” or celebrate “Hour of Code” trivialize the power of programming. Engaging in the false complexity associated with teaching a new programming language every year (or faster) is also likely to deprive students of the exhilarating feelings that result from your program meeting or exceeding your expectations. Programming should be like learning to write, compose, make cinema, dance, etc…

Above all else, quality work takes time. What’s your hurry?

PS: Computer programming requires computers.

• • •

Get started learning to program by programming at Constructing Modern Knowledge 2020!

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.