What I Did on My Three Summer Vacations By Brian Silverman

By Brian Silverman

Illustrated by Peter Reynolds

Previously published in Mathematics and Informatic Quarterly (in Bulgaria) prior to this version appearing in the Fall 1998 issue of Logo Exchange. Volume 17. Number 1.

We finally did it. We made it through the maze in Montreal’s Old Port in eleven minutes. There’s a really good chance that our time is the all-time record!

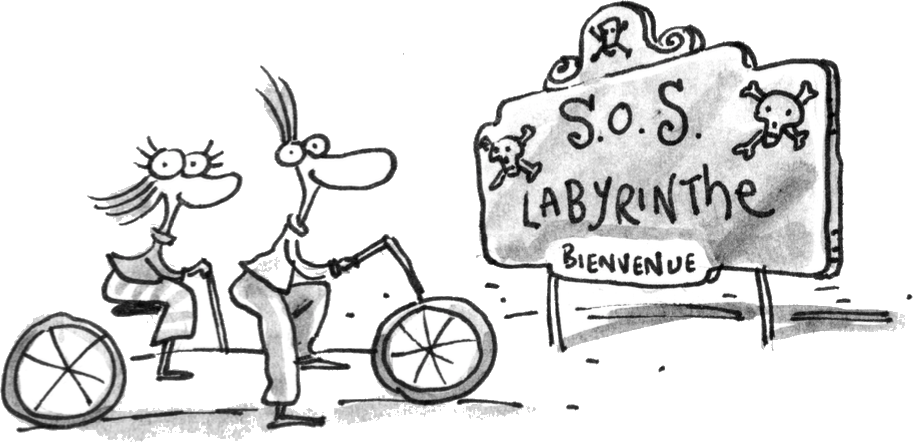

It all started a few years ago when my daughter, Diana and I were biking and found ourselves in Montreal’s Old Port. There was a new attraction called S.O.S. Labyrinthe, that promised a pirate adventure. It turned out to be a giant indoor maze in an old warehouse building with a handful obstacles with a pirate theme. The “pirates” were kids on roller blades providing help to the desperately lost and confusion to the rest of us.

It all started a few years ago when my daughter, Diana and I were biking and found ourselves in Montreal’s Old Port. There was a new attraction called S.O.S. Labyrinthe, that promised a pirate adventure. It turned out to be a giant indoor maze in an old warehouse building with a handful obstacles with a pirate theme. The “pirates” were kids on roller blades providing help to the desperately lost and confusion to the rest of us.

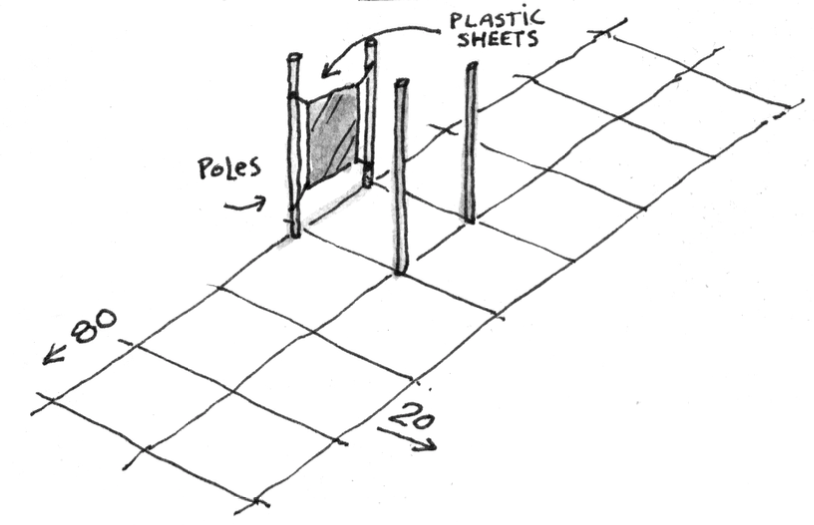

The maze is a twenty-by-eighty grid of about two metre squares. The walls are made of thick plastic sheets hung between poles that are placed at the grid points. Four small sections of the maze have been built up to resemble a ship’s bridge, an engine room, a cargo hold, and lockers for the crew. These four checkpoints have hidden stampers to stamp a card received when you enter the maze.This card is also time-stamped when you first enter then maze and again when you leave.

When Diana and I first tried we got lost almost immediately. It took us about an hour and twenty minutes to find our way out and get all the stamps we needed. Despite being lost most of the time we enjoyed it so much that we went back the following week. This time we brought my son Eric along because he’d missed the first time through. The second time, to avoid getting lost, we decided to follow a set of simple rules that, as any little robot will tell you, can help to get you out of most mazes.

The rules are:

- turn right whenever you can

- turn around when you reach a dead end.

That’s all there is to it and it actually works. We followed the rules and managed to make it through the maze in about twenty two minutes. When we finished the pirate behind the desk put our names on the board as the group that had the best time of the day. He mentioned in passing that it was a better time than he sees most days.

That’s all there is to it and it actually works. We followed the rules and managed to make it through the maze in about twenty two minutes. When we finished the pirate behind the desk put our names on the board as the group that had the best time of the day. He mentioned in passing that it was a better time than he sees most days.

The challenge at this point was obvious. Our goal was to get the best time ever. We only had to figure out how. I had a plan that I thought would be pretty simple. However, as is almost always the case, it didn’t turn out to be as simple as I’d initially imagined. The plan was this: Go through the maze twice. The first time through bring along a little computer to record our path. Then go home, draw a map, find the best route and go back the following day and go through running as fast as we can.

There were a couple of immediate problems. The first one was pretty easy to resolve. How could we be sure that the maze didn’t change on us between the first run and the second? (The plastic panels are moved on a regular basis to keep the maze from staying the same.) A couple of phone calls and oblique questions later, we’d found out that the maze is only changed once a week, on Thursday night. The second immediate problem was trickier to resolve. Our plan required little computers to record our path. We didn’t have any little computers. Even if we did we wouldn’t know how to make them record paths.

My friends at MIT had little computers. We’d been working for a few years on making “programmable LEGO bricks”. At that time we were at the point where we’d had a couple of prototypes that had worked for a bit but none of them were reliable enough for the task. However as a result of a sort of spinoff of that project there were some little computer boards around that weren’t much bigger than a deck of cards. I asked my friend Randy Sargent if I could borrow one. He mailed it to me and I had it within a few weeks. Unfortunately by then the season was over and the project would have to wait until the next summer.

During the course of the winter a couple of things happened. One was that I had a lot of fun programming the little computer board I’d received. Over Christmas I played with making a tiny version of Logo. By New Year’s we had Logo programmable LEGO robots that didn’t need to be attached to a big computer. At the same time Randy had been working on perfecting a new programmable brick. By the following summer these came together and we had a programmable brick and a logo program for saving information about where in the maze we’d been.

Little computers are pretty stupid. We would have liked to have been able to just carry one along and have it remember where it had been. But the little computer wasn’t up for the task. What we did instead was attach a couple of pushbuttons to it. One to click the number of “squares” we’d gone forward, the other to click in the amount that we’d turned at each corner.

The summer mostly slid away before we got around to trying a second run. When we did get around to it, it was just Eric and me. Before getting into the maze we’d attached the brick to his belt, run some wires up his shirt and down the sleeves to the pushbuttons in his hands. Unless you were looking hard you wouldn’t have noticed anything suspicious. We scoped out the maze counting out loud on the straightaways and yelling out directions at the corners. People looked at us a bit strangely in general and were particularly confused and curious when we had to bring out the brick for minor adjustments.

The summer mostly slid away before we got around to trying a second run. When we did get around to it, it was just Eric and me. Before getting into the maze we’d attached the brick to his belt, run some wires up his shirt and down the sleeves to the pushbuttons in his hands. Unless you were looking hard you wouldn’t have noticed anything suspicious. We scoped out the maze counting out loud on the straightaways and yelling out directions at the corners. People looked at us a bit strangely in general and were particularly confused and curious when we had to bring out the brick for minor adjustments.

We didn’t do too well on that round. The brick started misbehaving about three quarters of the way through. And even if it hadn’t, the recorded data had lots of mistakes in it. With a lot of guessing and processing we were able to construct about a quarter of the map but no more. Since it was late summer we gave up again for the year figuring we’d pick it up again the following year.

The next winter was a good one for programmable bricks. When we did the second run there were only five working bricks in the world and even those five needed a fair amount of babysitting. By the next summer, there had been several new iterations of the design (largely the work of Fred Martin) resulting in dozens of working bricks that were solid enough that we wouldn’t have to worry too much about hardware failures for the next round.

Also, during the winter there was plenty of time to think about what went wrong the previous summer. The main problem was that mistakes in clicking the buttons led to so much distortion in the map that it was completely useless. The maze is so big, (more than a thousand straightaways and turns), that it’s impossible to do the kind of recording that we did without making mistakes. We thought a bit about eliminating mistakes but decided instead to run the experiment with several programmable bricks simultaneously, do the recording several times separately then regroup and compare results.

As it turns out, Randy and another friend, Carl Witty were planning to come to Montreal towards the end of the summer to show off their robots at an artificial intelligence conference. They arrived with a car full of computers, tools, and robot parts. Their robots all come with cameras connected to electronics that can discriminate colors. Their demos included robots chasing balls and each other at high speeds. It seemed only natural to get them involved in the third round.

We had a lot of discussion about whether or not we could use the vision systems they had in their robots for more automatic data gathering. We decided not to because even if we could resolve all the computer issues, we weren’t sure that we had enough batteries for all of the needed electronics for the time it’d take. We did decide, however, that since they had brought along several miniature cameras we’d take a video record of first trip through and use that to help interpret the data we’d get from the computers.

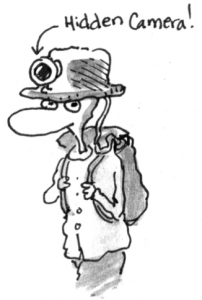

Carrying a camera around a maze really didn’t seem subtle enough. Instead we took the camera and sewed it into a hat with only the lens sticking out the front. The camcorder fit neatly in a backpack. By the time we were ready to go, Carl, Randy and I each had a programmable brick rubber banded to our belts and Eric had a camera in his hat. The data gathering run took about two hours and was pretty boring. The bricks kept disagreeing with each other but we ignored this because we decided to sort it all out later. Eric, originally worried that he’d attract too much attention with the camera ended up not being able to convince anyone that he actually had one.

Carrying a camera around a maze really didn’t seem subtle enough. Instead we took the camera and sewed it into a hat with only the lens sticking out the front. The camcorder fit neatly in a backpack. By the time we were ready to go, Carl, Randy and I each had a programmable brick rubber banded to our belts and Eric had a camera in his hat. The data gathering run took about two hours and was pretty boring. The bricks kept disagreeing with each other but we ignored this because we decided to sort it all out later. Eric, originally worried that he’d attract too much attention with the camera ended up not being able to convince anyone that he actually had one.

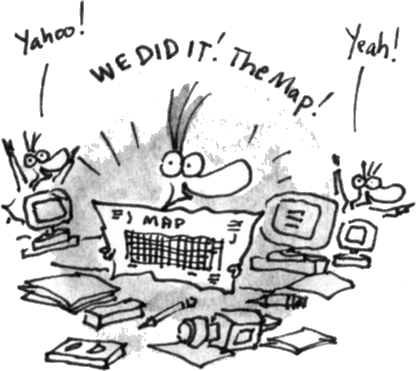

We brought the electronics home, dumped the data to three separate laptop computers and then spent an evening that didn’t quite turn into an all nighter trying to make some sense of it. For hours there was Randy, Carl, and I each with our own computer bouncing sequence numbers, grid locations, and reports of similarities and differences in data between us. My wife Erlyne and the kids watched for some of this, enjoyed part of the video but abandoned us when it seemed that we’d really fallen off the deep end. We persisted and after spending some time getting a feel for the method to the madness we decided to systemically play through the video noting when everything looked to be working and stopping the tape and fudging when it didn’t. Our stamina ran out before the tape did and we gave up for the night with about three quarters of the map in place.

The next morning, we all felt refreshed and raring to go. In less that two hours the printer was churning out copies of a complete maze map . We were about to set off when Eric asked why each of us had to go to get stamps at each of the places rather than splitting up the job. We realized pretty quickly that he had a point. There was a rule against going through the walls. There wasn’t a rule against the cards with the stamps going through the walls. It took us about a half an hour of staring at the map and thinking to come up with a plan that involved three teams and three relay points to pass the cards along like a baton in a relay race. Eric and I had the first stretch, passed the cards to Randy and then headed off to where Randy would pass them back after having met Carl twice along the way.

It all worked like clockwork. The maps were accurate, the plan workable. Eric and I had the first stamp in less that two minutes and found Randy in another two. When we called him through the plastic wall he didn’t answer but his hand appeared. He said later that a pirate was standing right beside and he was trying to not attract any attention. After the handoff we headed to the final relay point where we met up with Carl and got the cards through the wall from Randy. From there it was just a quick run to the end to get the last time stamp. It had taken eleven minutes, much less time than we had imagined possible.

We went to see the pirate at the desk. The board of daily winners wasn’t around any more. We showed him our card that confirmed that we’d done it in eleven minutes. He said that if we did it that fast we must have cheated. Maybe it’s true. Throwing that much technology at a problem may be cheating. On the other hand, it may just be another way of solving it

About the author

Since the late 1970s, Brian Silverman has been involved in the invention of learning environments for children. His work includes dozens of Logo versions (including LogoWriter & MicroWorlds), Scratch, LEGO robotics, TurtleArt and the PicoCricket. Brian is a Consulting Scientist to the MIT Media Lab, enjoys recreational math, and is a computer scientist and master tinkerer. He once built a tictactoe-playing computer out of TinkerToys. Brian is a longtime faculty member of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute.

You can also visit Brian’s Wikipedia page here.

About the illustrator

Peter H. Reynolds co-founded FableVision, Inc., in 1996 and serves as its Chairman. Mr. Reynolds produces award-winning children’s broadcast programming, educational videos and multimedia applications at FableVision, Inc. He served as Vice President and Creative Director of Tom Snyder Productions for 13 years.

He is also an accomplished writer, storyteller and illustrator, and gets his enthusiasm and energy to every project he creates. His bestselling books

Peter Reynolds was a guest speaker at the 1st and 10th annual Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute.

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.