Gary Stager on International Ed Comparisons

John Dewey is Ours!

By Gary Stager

District Administration, Apr 2005

Put on your dunce caps! It’s international education comparison season again. I know. I know… Eritrea is kicking our butt in long division. If we don’t get tough quickly, all of our best fast-food jobs will be outsourced overseas.

During this somber season of atonement, assorted windbags take to the airwaves to decry the callous incompetence of American teachers and to label our students as fat, lazy and stupid. We learn that country X focuses on the basics; country Y spends more time on fewer topics; while country Z has a longer school year. Don’t you just love how after careful review of the data, the prescription for American public schools is always more testing, increased sanctions, louder name-calling and longer seat-time?

We know that simplistic proclamations about superior schools far away are incomplete at best, yet we continue to wring our hands about our inferiority. Japan is one of the favorite pedagogical bogeymen, but on a trip to Tokyo I witnessed four people employed to complete every retail transaction and two women required to operate an automatic elevator. I suspect that the four people making change at every department store checkout counter or the two women piloting one elevator did not succeed in calculus class. Like in Houston, students who might lower the average must just disappear.

While others can challenge their validity, the greatest risk posed by the international education comparisons is the underlying assumption that learning is (or should be) uniform. This premise is absurd and destructive for every state engaged in the standardized arms race. No human endeavor can or should be standardized. This is especially true across different cultures with dissimilar needs, goals, motivations, resources and belief systems.

The Stager Perspective

My work in public and private schools across a dozen or so countries entitles me to proclaim myself a scholar on global educational comparisons. My experience and humble analysis leads me to the following conclusion. Schools stink everywhere!

As long as citizens around the world strive to embrace the following myths and practices schools will continue to lose relevance and offer fewer benefits to children.

Artificial curricular hierarchy

The notion that a committee of bureaucrats can prescribe a specific sequence of curricular topics and skills for all learners defies everything we know about learning theory and will always lag behind societal shifts.

Assuming knowledge is static

Just as every learner is different, the nature of knowledge is fluid. Educational success is not measured by recitation and recall.

Testing is not teaching and teaching is not learning

Until we abandon the obsession with quantifying knowledge without even engaging a discussion of, “what we mean by learning,” schools will continue to treat children as rounding errors.

Barbaric conditions

Rows of uncomfortable desks nailed to the floor, bells, grades, age segregation, decontextualized content, sorting by similar levels of incompetence and zero-tolerance policies must give way to more flexible learning environments.

Communication is weak

Parents, still largely unwelcome educational partners, find it increasingly difficult to receive timely answers to simple questions despite enormous investments in data aggregation and school-to-home accountability systems.

It doesn’t ultimately matter if you agree with my hypothesis about the ill-health of schools and schooling. What you must celebrate is that the American ideal is for every child to enjoy a free and excellent K-12 education, followed by unparalleled opportunities for higher education. While our practice does not always measure up to our rhetoric, our democratic ideals are noble and our schools have served many children well. Rather than waste our energy worrying about global competition we should rededicate ourselves to helping every child reach their potential as a well-rounded human with a thirst for knowledge and creative expression.

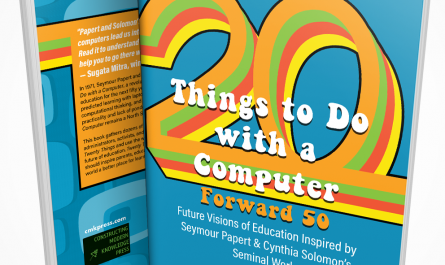

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.