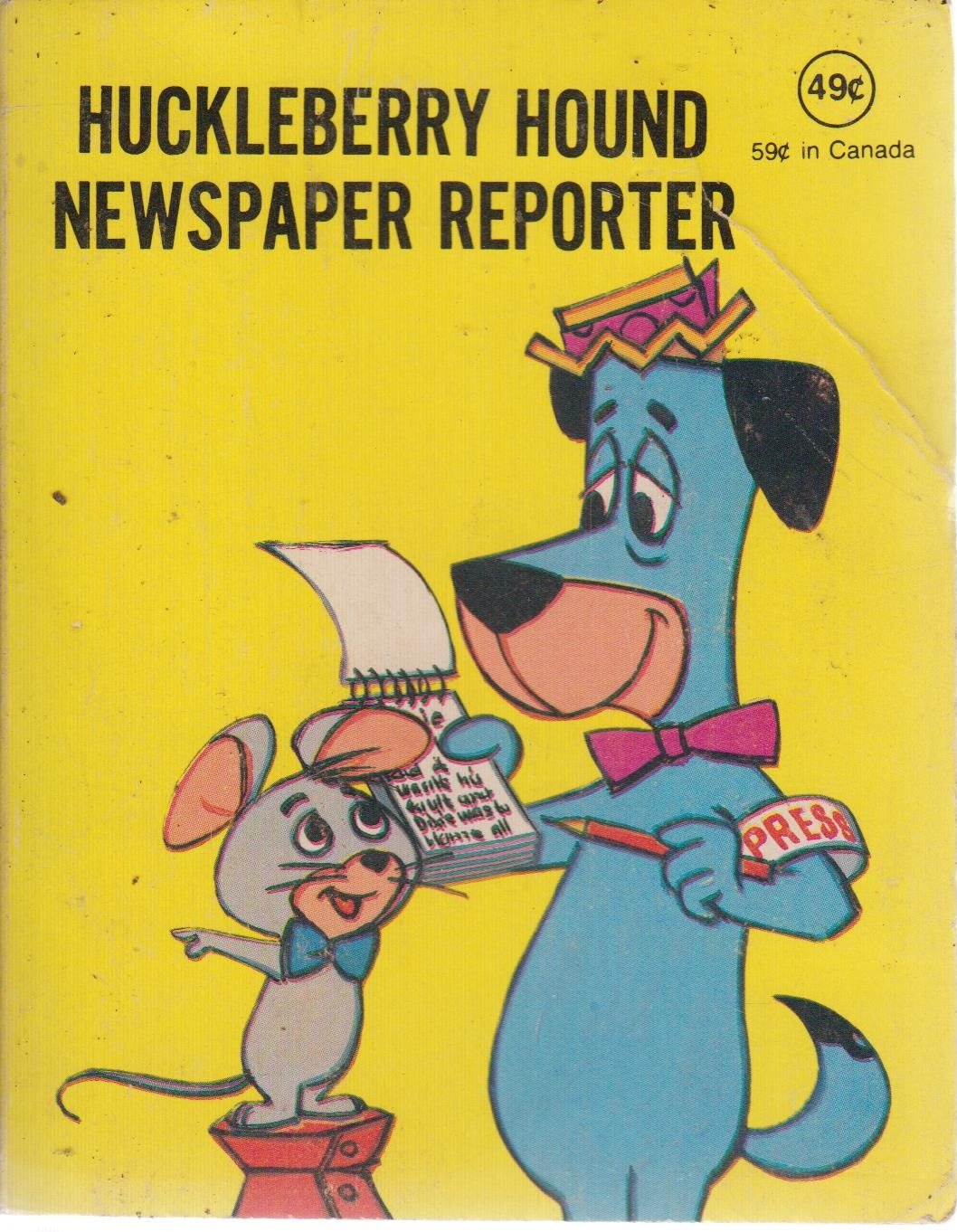

I recently received interview questions by a cub reporter in the heartland. Paradoxically, the nature of the questions made answering a challenge. Here’s my attempt.

I recently received interview questions by a cub reporter in the heartland. Paradoxically, the nature of the questions made answering a challenge. Here’s my attempt.

How would you define STEM education?

Quite literally, STEM is an acronym meaning science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. To the extent that there is anything new to be found in STEM, it is a recognition that the nature and process of both science and mathematics have changed dramatically outside of school and that educational institutions may wish to reflect such advances. The T in “Technology” is unfortunate since it really should mean computing – programming computers to create models and solve problems otherwise impossible. The “T” certainly doesn’t refer to a Thermos or Pez dispenser, arguably both less protean technologies.

The E for “Engineering” is also a new addition to the curriculum. Young children are natural engineers. They enjoy an intellectual relationship with materials, people, and even ideas. They tinker and explore. They test hypotheses and push limits. Engineering is the concrete manifestation of theoretical principles. You test a hypothesis or try something. If it works, you’re inspired to test a larger theory, ask a deeper question, decorate, refine, or improve upon your innovation. If you are unsuccessful, one must engage in the intellectually powerful process of debugging. Traditionally, the only people permitted to have engineering experiences were the students who compliantly succeeded over twelve or fourteen years of abstraction. Engineering is the dessert you enjoy after your asparagus diet of school math and science.

The addition of intensely personal and playful pursuits like computing and engineering democratized science and mathematics learning while affording children the chance to do real math and science. Students should be scientists and mathematicians, rather than be taught math or science, especially when that curricular content is increasingly irrelevant, inauthentic, and noxious.

Would you say STEM education is important? If so, why?

If the motivation for STEM is some misplaced fantasy about job preparation or STEM is merely a buzzword designed to offer an illusion of progress, than STEM is not important. If we want scientifically and numerate students, some of whom might fall in love with making sense of the universe, while recognizing the changing nature of knowledge, than STEM has intense value.

If our goals are no more ambitious than raising stupid test scores, then kids should have rich engineering and technology experiences in order to be more active learners.

Dr. Stephen Wolfram, arguably the world’s greatest living mathematical and scientist, says that for any intellectual domain, X, there is now or soon will be a branch of that discipline called, “Computational X.” That new branch of the discipline represents the vanguard of that field, the most interesting ideas, and likely the better paying jobs as well.

Should schools have STEM programs? How are they beneficial to students?

If schools are going to bother teaching what they call math and science than they should embrace the new ideas, content, and processes of STEM. It is critical to engage students in authentic experiences since Jean Piaget taught us that “knowledge is a consequence of experience.”

Schools should stop using the term “program.” Program implies a high probability of failure and therefore obscures the urgency to create a new intellectual diet for children. To the extent that one program siphons resources from another, than STEM is far less important than adequate funding for art and music education.

What does the future of STEM education look like to you?

Schools need to prepare students to solve problems that their teachers never anticipated. In 1989, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, the world’s least radical organization, stated that 50% of all mathematics has been invented since WW II. Let’s assume that that percentage is even higher thirty years late. None of that new mathematics made possible by computing and the social science’s demand for number can be found anywhere near a K-12 classroom and that is a sin.

Schools need to prepare students to solve problems that their teachers never anticipated. In 1989, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, the world’s least radical organization, stated that 50% of all mathematics has been invented since WW II. Let’s assume that that percentage is even higher thirty years late. None of that new mathematics made possible by computing and the social science’s demand for number can be found anywhere near a K-12 classroom and that is a sin.

New technology and materials afford us with the opportunity to not only teach kids the things we’ve always wanted them to know (regardless of merit), but for children to learn and do in ways that were unimaginable a few years ago.

The better question to ask is, “Who could possibly be against STEM?”

Veteran educator Dr. Gary Stager is co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Learn more about Gary here.

Veteran educator Gary Stager, Ph.D. is the author of Twenty Things to Do with a Computer – Forward 50, co-author of Invent To Learn — Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, publisher at Constructing Modern Knowledge Press, and the founder of the Constructing Modern Knowledge summer institute. He led professional development in the world’s first 1:1 laptop schools thirty years ago and designed one of the oldest online graduate school programs. Gary is also the curator of The Seymour Papert archives at DailyPapert.com. Learn more about Gary here.